Products, services and equal competition

Finnish Food Authority | National Supervisory Authority for Welfare and Health | Finnish Patent and Registration Office | Centre for Economic Development, Transport and the Environment

Food business operators under target-specific control

Source: Finnish Food Authority

Every grocery store, restaurant, café and establishment that produces foods (food business operator) is a separate target of food control. If a food business operator engages in more than one food business activity, it is registered in the category of its principal activity. The category of “food service” includes cafés, restaurants and mass caterers. Figure 1 presents the number of sectors included in the scope of food control.

Food control is risk-based and planned

Risk-based food control means that high-risk food business operators are subject to greater control than low-risk operators. For instance, a food establishment that produces meat products is classified as a higher-risk food control target than, say, a kiosk that sells packaged foodstuffs. In food control, the control targets are categorised into various risk categories, and the control frequency of each group is determined on the basis of the risk categorisation. For this reason, some control targets are inspected several times a year, whereas other control targets may go several years between inspections.

A total of 37 per cent of all objects of control were inspected last year. Figure 2 shows the percentage of inspected objects of control by sector: up to 90% of high-risk objects and less than 20% of low-risk objects have been inspected.

Results of food control are easily available online and by the doors of food business operators

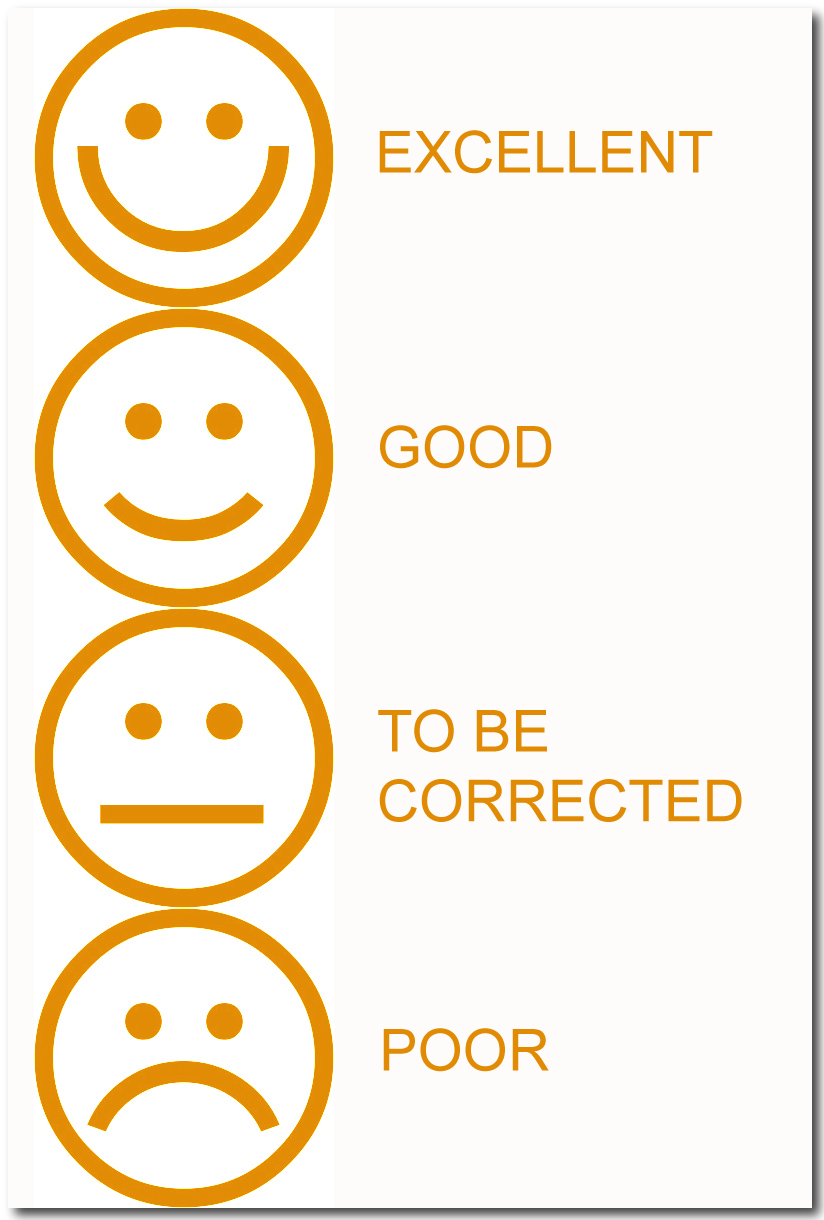

Food control is carried out systematically across the country under the OIVA (Finnish Smiley) system. The food control authority inspects selected aspects of the control target during each inspection. The results are published as an OIVA report. There are four possible results: excellent, good, to be corrected and poor.

OIVA scale. Picture: oivahymy.fi/en [.fi]›

The results of OIVA inspections are published at the entrances of inspected food business operators and on their websites. The OIVA results of food business operators can also be found at oivahymy.fi/en [.fi]›.

Results of OIVA inspections based on a scale from A to D

Figure 4 presents a breakdown of the OIVA grades of grocery stores and service locations, as well as the total grades of all inspected food business operators. So far, annual differences between the grades of different operator groups have been minor. More than 83% of the objects of control received the grade excellent or good last year, while fewer than 17% of objects received the grade to be corrected or poor.

If a food business operator receives the grade to be corrected or poor, the authority will often issue an order or use another administrative coercive measure to ensure that the non-compliance is corrected. All companies receiving the grade to be corrected or poor will be subject to a follow-up inspection.

Administrative coercive measures are taken to address activities that do not comply with the law

Food control authorities are obligated to ensure that any situation that does not comply with the law is rectified. The Food Act lays down administrative coercive measures that are to be employed when necessary. Last year, 190 decisions on administrative coercive measures were made (figure 5). The most commonly employed administrative coercive measure is an order.

Reliability and compliance with obligations of food business operators

A business operating in the food industry must comply with food legislation to ensure that the safety of consumers is not compromised and that consumers are not misled. The reliability of financial activities is also assessed by monitoring the payment of taxes and other statutory fees, for example.

Issues with meeting statutory obligations may reflect a shadow economy risk, and operators who fail to comply with their statutory obligations may also fail to comply with the requirements laid down to ensure food safety.

By combining the data from a compliance report with the data from an OIVA (Finnish Smiley) assessment, the reliability of an operator can be assessed from both an economic and a food safety perspective, thus achieving a comprehensive idea of the company’s operations. These insights can be used to target control measures, and they are also helpful when investigating suspected offences in the food supply chain.

Suspected offences and requests for investigation regarding business operations related to the food supply chain

The compilation of suspected offences in the entire food supply chain and requests for investigation to the criminal investigation authorities started in 2021. In addition to food business operators, the food supply chain includes animal and plant production farms and feed, fertiliser, seed and by-product industry operators, among others.

A single recorded suspected offence or request for investigation may involve suspected offences from several legislative sectors and also several different offences. The most common offences in the case of the food supply chain are health offence, marketing offence, registration offence, animal welfare offence and aggravated animal welfare offence, causing a risk of spreading an animal disease, degradation of the environment, fraud and aggravated fraud, as well as forgery and aggravated forgery. Figure 6 shows the number of suspected criminal offences and the number of submitted requests for investigation brought to the attention of the Finnish Food Authority.

Last year, the most typical suspected offences involved a series of suspected offences related to animal production in primary production and cases where it was suspected that food had been produced outside the scope of food control under inappropriate conditions.

The Finnish Food Authority’s food control development project uncovered dozens of food businesses operating outside the food control register and thus completely outside the scope of food control. Information about these businesses was obtained in cooperation with the Finnish Tax Administration and municipal food control units. Some of the cases have been dealt with by way of administrative measures, while a request for investigation has been or will be submitted to the pre-trial investigation authority in others.

The food control statistics should be examined by comparing them with the observations and statistics of other authorities presented in this snapshot. This makes it possible to find common features or even mechanisms of action between different phenomena or within a single phenomenon.

Alcohol administration is combating the shadow economy

Source: National Supervisory Authority for Welfare and Health (Valvira)

Alcohol administration means the overall system of licensing administration, supervision and steering comprising the National Supervisory Authority for Welfare and Health (Valvira) and the Regional State Administrative Agencies (AVI), which act as the alcohol authorities. The Regional State Administrative Agencies supervise the serving and retail sales of alcoholic beverages in their areas. Valvira attends to nationwide supervision and the provision of guidance for the Regional State Administrative Agencies on supervising the serving and retail sales of alcohol.

The core task of the alcohol administration is to prevent the harm caused by alcohol to its users, other people and society at larger, by supervising and limiting alcohol-related business activities. This core task provides a solid basis for the network of authorities combating the shadow economy.

The Alcohol Act emphasises the role of self-monitoring, and it requires the licence holders operating under the Alcohol Act to prepare a self-monitoring plan to support their operations. A good self-monitoring plan can prevent many practical problems, and it is important that the licence holders take their self-monitoring obligation seriously.

Major changes made to the information processing features of the alcohol trade register

The e-service function of the new alcohol trade register (Allu) became operational in April 2023. Allu is maintained by Valvira and Regional State Administrative Agencies, and the details of alcohol operators, alcohol licences and alcoholic products, as well as their production and deliveries are stored in the register. The register is used by such parties as holders of alcohol serving licences, retailers, wholesalers, producers, industrial users and the authorities.

Allu produces analysed information on the supervision of serving and retail sales, the reliability of business operators, and the determination of their financial prerequisites. The information also provides the basis for official alcohol statistics, as well as the information and register services on alcohol matters. With the introduction of the e-service, the alcohol administration can now administer licences and process supervisory matters on a more digital and real-time basis. Development of the updated system will enhance cooperation between the authorities, improve case management and allow information to flow more smoothly.

Number of cases processed by the alcohol administration back to covid period levels

In the years before the overhaul of the Alcohol Act, Regional State Administrative Agencies processed, on average, roughly 9,000 cases related to serving or retail sales of alcohol. As a result of the reform of the Alcohol Act in 2018, the number of licensing cases processed by the alcohol inspectors of the Regional State Administrative Agencies increased by several thousand. During the exceptional period of 2020 and 2021, the number of processed cases dropped below 8,000. This change can partly be attributed to the reallocation of alcohol inspectors’ tasks to supervisory and preventive activities in accordance with the Communicable Diseases Act. Furthermore, because most events requiring a temporary serving licence were cancelled, no processing of licences in connection with them was required.

In 2022, the number of processed cases returned to the levels registered before the overhaul whereas in 2023, the number of processed cases dropped to 8,000. However, it is too early to say whether the uncertainties arising from the business impact the willingness to apply for licences or whether the decline has been caused by changes in the registration practices resulting from the alcohol trade register reform. (Figure 1).

The number of serving licences increased while the number of retail sales licences decreased

In the years preceding the reform of the Alcohol Act in 2018, the number of licences to serve alcohol remained fairly stably around 8,300 serving licences, after which the number of licences increased significantly. Rate of quantitative increase slowed down in 2020 but accelerated again in the period 2021–2023. At the end of 2023, there were a total of 9,816 valid serving licences in Mainland Finland. This was 100 more than at the end of 2022 (Figure 2). The increase in the number of alcohol serving licences can probably be attributed to the easing of requirements for obtaining a serving licence; for example, the responsible manager only needs to possess an alcohol proficiency certificate. Licences have also been applied for as a secondary service for other activities.

The number of retail sales licences (sales of alcoholic beverages of at most 5.5% between 9 am and 9 pm) decreased steadily before the reform of the Alcohol Act. With the reform of the Alcohol Act, the total number of alcohol retail sales licences took an upturn. The change can be attributed to the granting of retail sales licences to holders of serving licences and to producers of craft beer and farm wine. At the end of 2023, alcoholic beverages could be purchased for takeaway from a total of 4,699 outlets in Mainland Finland. This was 174 fewer than at the end of 2022 (Figure 2). The decrease in the number of retail sales outlets can partially be attributed to the concentration of the business in shopping centres and the new statistical methods introduced as part of the alcohol trade register reform. Takeaway licences granted to serving premises are not included in the retail sales statistics.

Alcohol administration has successfully combated the shadow economy – statistical methods were updated again

To assess the effectiveness of the measures taken to combat the shadow economy, the focus in the supervision is also on measures to ensure that licence holders have the prerequisites to carry out their business operations. Between 2012 and 2021, Valvira compiled comparable statistics on supervision carried out to combat the shadow economy. As of 1 January 2022, we updated the compilation of the statistics on supervision carried out to combat the shadow economy to ensure that they are in accordance with the Alcohol Act. As of 1 January 2023, statistical data batches were split into licensing administration matters and supervisory matters.

Licensing administration statistics cover the measures carried out in connection with the applications for new alcohol serving and retail sales licences whereas the statistics on supervisory matters cover the measures arising from existing licences. The data batches compiled into statistics produce an overview of the measures taken by the alcohol administration to combat the shadow economy and the effectiveness of the measures.

Combating the shadow economy is one part of the extensive responsibilities of the alcohol administration. The measures taken by the alcohol administration to combat the shadow economy in 2023 can be regarded as highly successful, considering the impacts of the exceptional period still affecting the branch, the payment and operating relief granted to the entrepreneurs, and the decrease in the personnel resources of the alcohol administration.

Statistics on combating the shadow economy – supervision

Table 1 shows the supervisory measures taken by the Regional State Administrative Agencies in 2023 to combat the shadow economy, in which the focus was on existing licences. The summary describes the number of supervisory measures opened to identify the financial prerequisites in each region. In addition, it indicates the number of measures related to the investigation of supervisory measures and their results, including requests for clarification sent to licence holders, deadlines set and guidance issued, the cancellation of serving and/or retail sales licences, and payment arrangements and plans agreed as a result of supervisory measures, as well as outstanding taxes paid.

In the years before 2023, an average of 164 requests for clarification were made each year, and as a result, about €1.5 million in outstanding taxes were paid. In 2023, a total of 195 supervisory cases were opened and they led to 124 requests for clarification. The tax debt payments resulting from the measures totalled about €1.2 million.

Statistics on combating the shadow economy – licensing

Table 2 shows the supervisory measures taken by the Regional State Administrative Agencies in 2023 to combat the shadow economy as part of the licence application process. The summary shows the number of licensing cases opened to examine the financial prerequisites in each region. It also shows the number of measures taken to investigate licensing matters and their results, including requests for clarification sent to licence holders, cancellation of licences, negative decisions, licences granted on a temporary basis, licences granted in accordance with the application, payment arrangements and programmes introduced as a result of completed licensing cases, as well as the tax debts paid.

In 2023, a total of 127 licensing cases were opened and they led to 115 requests for clarification. The tax debt payments resulting from the measures totalled about €610,000.

Accuracy of Trade Register records is monitored

Source: The Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment

The National Board of Patents and Registration (PRH) is responsible for maintaining and monitoring the accuracy of information submitted to the Trade Register. The number of Trade Register offences brought to light and of Trade Register submissions investigated on a risk basis are indicative of the possible amount of shadow economy activity.

PRH launched enhanced investigations of Trade Register submissions in March 2016, and they were continued in 2017, 2018 and 2019. This practice has helped to prevent irregularities. In 2019, there were no notifications giving reason to suspect a registration offence. Enhanced control was targeted at notifications of changes in limited liability companies or cooperatives with details of a new Board of Directors, managing director or building manager. The aim of enhanced processing is to identify whether the decision issued is appropriate. If certain criteria were met, PRH requested a copy of the deed of sale of shares to be attached to the notification or called the company to verify the accuracy of the notification.

In 2020, the systematic enhanced control of notifications was discontinued, partly for resource-related reasons, and partly because the use of electronic services increased clearly. Enhanced control was conducted a few times a year by means of spot checks. During the enhanced control conducted in October 2020, there were no notifications giving reason to suspect a registration offence. In November 2021, a few cases of misconduct were discovered, as a result of which PRH restarted the enhanced processing of notifications. Enhanced control concerns notifications of changes in limited liability companies or cooperatives with details of a new Board of Directors, managing director or building manager. If certain criteria are met, the registration authority aims to determine the correctness of the notified circumstances by the aforementioned means.

In 2022, the enhanced control of notifications was continued using criteria defined based on risks. Enhanced control was targeted at notifications of changes in limited liability companies or cooperatives with details of a new Board of Directors, managing director or building manager. A few more abuse cases were discovered than in the previous year. Targeted control helped prevent any incorrect data from being registered. In 2023, targeted risk-based control measures were applied to certain notifications of changes. No actual cases of misconduct were detected in 2023.

Phenomena related to residence permit applications for entrepreneurs more diverse

Source: Uusimaa Centre for Economic Development, Transport and the Environment

An entrepreneur’s residence permit is granted in two stages: the Uusimaa Centre for Economic Development, Transport and the Environment (ELY) makes an interim decision before the final decision is made by the Finnish Immigration Service. The interim decision is made assessing the profitability of companies and the preconditions for the livelihoods of permit applicants.

In 2023, the Uusimaa ELY Centre issued a total of 1,104 interim decisions, of which 48% were negative. The share of negative interim decisions increased by 8% from the previous year. Interim decisions on first residence permits accounted for 29% and subsequent permits 71% of all interim decisions.

Many reasons for negative decisions

A negative decision is not a direct indication of shadow economy activities, while some of these situations may involve the shadow economy and economic crime as underlying factors. The most common reasons for negative interim decisions include deficiencies in complying with statutory obligations, irregularities in the payment of wages, deficient or erroneous accounting, or a non-viable business idea and lack of profitability, which mean that the applicant cannot ensure their livelihood by means of their business operations.

The Uusimaa ELY Centre works with other authorities to combat the shadow economy and economic crime. Any deficiencies and neglects discovered during the processing of entrepreneurs’ residence permit applications were reported to the Finnish Immigration Service, the Regional State Administrative Agencies, the Finnish Tax Administration and the Police of Finland.

Disguised employment, underpayment, labour exploitation, black market for subcontracting, and the increase in the number of middlemen used without any business justification are phenomena that were highlighted in negative interim decisions. The volume of disguised employment and observations of labour exploitation increased in the past year. The ELY Centre cannot adopt a positive view in its assessment on underpayment or avoidance of statutory employer obligations. If the services of a self-employed individual are used, the calculated hourly wages must be higher than those of employees, because the costs and livelihood of the self-employed person must be covered. Paid services by external providers were still found in the applications.

Negative interim decisions by nationality

Applications for entrepreneurs’ residence permits were received from citizens of 70 countries. The largest number of applications was received from citizens of Russia, China and Pakistan. As in previous years, Russian and Chinese were the most common citizenships in entrepreneurs’ residence permit applications. Relatively, the most negative decisions were made regarding citizens of Iraq who also made up the sixth largest group of applicants out of all nationalities.

Negative interim decisions by principal activity

Applications for entrepreneurs’ residence permits include companies in a large range of sectors. In 2023, applications included 180 different principal activities. In terms of quantity, the largest principal activities were the restaurant industry (restaurants/cafeteria-restaurants), other postal, delivery and courier activities, and the IT industry (software development, programming and consulting). Figure 3 presents the ten principal industries that had the most negative interim decisions. The share of negative interim decisions was the highest in the industries taxi operation, and restaurants and cafés.