Tax residency, nonresidency and residency in accordance with a tax treaty – natural persons

Key terms:

- Date of issue

- 3/27/2023

- Validity

- 3/27/2023 - Until further notice

For more information about taking care of your tax matters in Finland, see the instructions at Work in Finland.

This is an unofficial translation. The official instruction is drafted in Finnish (Yleinen ja rajoitettu verovelvollisuus sekä verosopimuksen mukainen asuminen – luonnolliset henkilöt, record number VH/1482/00.01.00/2023) and Swedish (Allmän och begränsad skattskyldighet samt boende enligt skatteavtal – fysiska personer, record number VH/1482/00.01.00/2023) languages.

Under the provisions of the Income Tax Act (tuloverolaki, 1535/1992), taxpayers may either be resident taxpayers (generally liable to tax) or non-resident taxpayers (liable to tax, but with restrictions). The Income Tax Act also includes a number of special provisions on the scope of tax liability. Resident taxpayers, having unlimited tax liability, are people living in Finland, and correspondingly, non-resident taxpayers, with limited tax liability, are people living in other countries. Resident taxpayers pay taxes in Finland for income earned in Finland and income earned in other countries (= liability to tax on worldwide income). Non-resident taxpayers pay taxes in Finland on income earned in Finland only.

These instructions apply to the determination of the tax liability of natural persons pursuant to the Income Tax Act, as well as the determination of country of residence pursuant to a tax treaty. These instructions do not cover the taxation of income received by resident and non-resident taxpayers. For more information on these, please see the instructions on the specific type of income.

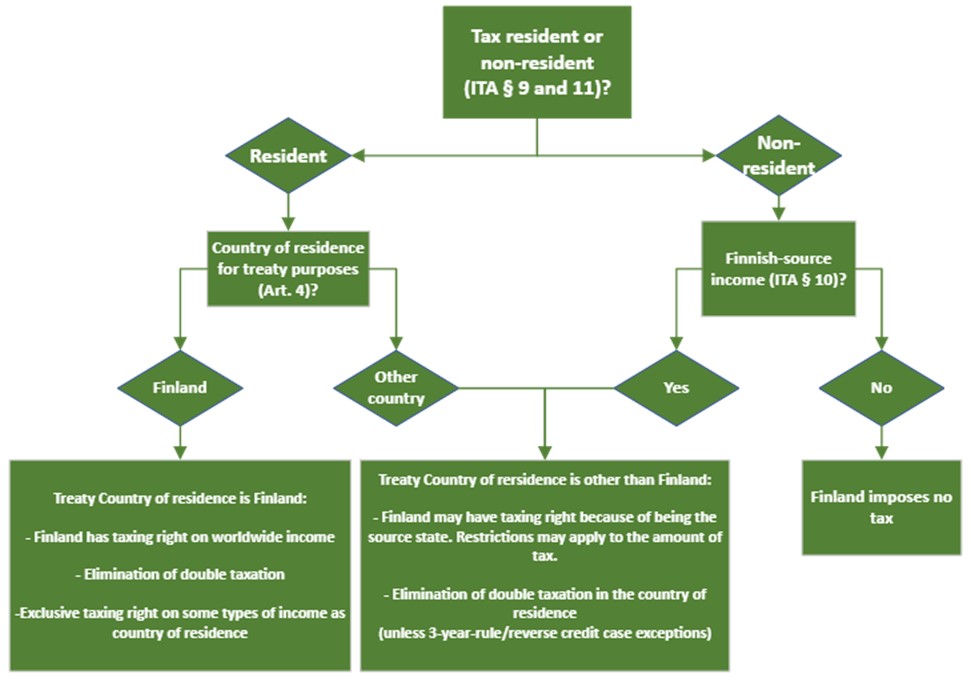

Updates were made to section 6 – Requesting nonresidency or country of residence pursuant to tax treaty, including more precise definitions. Other sections were revised only by inclusion of technical details. End of the final section is now followed by Annex 1 – Flowchart indicating impact on Finnish taxes of the individual taxpayer’s status and treaty country of residence.

For more information on the determination of the tax liability of organisations and the impact of tax treaties, please see the Finnish Tax Administration’s instructions Yhteisön yleinen ja rajoitettu verovelvollisuus (Resident and nonresident tax liability of corporate entities).

1 Introduction

According to section 9, subsection 1 of the Income Tax Act (tuloverolaki, 1535/1992, “TVL”), there are two tax liability groups in Finland, resident and non-resident taxpayers. Both the scope of the tax liability and the assessment procedure are different for resident and non-resident taxpayers.

Pursuant to the Income Tax Act, individuals living in Finland, i.e. resident taxpayers, are obligated to pay tax taxes in Finland for income earned in Finland and abroad (section 9, subsection 1(1) of the Income Tax Act). Hence, the tax liability in Finland is worldwide. Taxation is usually performed based on a tax return, and a variety of deductions may apply. In the case of a resident taxpayer, taxation is, as a general rule, carried out under the progressive scheme based on total income in accordance with the Tax Assessment Procedure Act (laki verotusmenettelystä, 1558/1995). Certain special groups make an exception to this rule, such as key employees as laid down in the Act on Tax at Source for Foreign Employees (laki ulkomailta tulevan palkansaajan lähdeverosta, 1551/1995) and employees of the Nordic Investment Bank.

Pursuant to the Income Tax Act, individuals living abroad, i.e. non-resident taxpayers, are only liable to pay tax in Finland for income earned in Finland. There is a list of income earned in Finland in section 10 of the Income Tax Act. However, the list is only an example. This means that many other categories and types of income that are not on the list can also be seen as sourced to Finland. However, the items of income that are listed are seen as sourced to Finland only within the limits set out by the wording of § 10 (in reference to the text of the act on income tax in Finnish and Swedish). In case-law and in tax assessment practice, examples of income that is not included in the list but is still seen as Finnish-sourced includes social security benefits from Finland i.e., maternity/paternity allowances, study grants, etc., accident insurance and motor vehicle insurance payments, a shareholder loan from a Finnish limited liability company and payments pursuant to a capital redemption policy or life insurance policy.

Non-resident taxpayers are taxed pursuant to the Act on the Taxation of Non-residents’ Income (laki rajoitetusti verovelvollisen tulon verottamisesta, 627/1978) or the “Tax at Source Act”. In most cases, the payer is obligated to withhold from a non-resident taxpayer tax at source independent of the amount of the income, which is also the final tax. The amount of the tax at source depends on the type of income. In the case of tax withheld at source, a tax return is usually not submitted and deductions do not apply. A tax return must be submitted, however, if the individual has income from which tax has not been withheld and tax must be imposed.

Some of the income earned by non-resident taxpayers is taxed pursuant to the Tax Assessment Procedure Act (laki verotusmenettelystä, 1558/1995). According to section 13 of the Tax at Source Act (856/2005, an amended regulation), pension income is such income, for example. A non-resident taxpayer may also submit an application on having the taxation of their earned income performed, instead of as tax at source, in accordance with the Tax Assessment Procedure Act in the same way as for individuals living in Finland, i.e. progressively based on the amount of total income.

Foreign citizens working in Finland as diplomats or on the payroll of specific international organisations are often resident taxpayers in Finland due to the length of their presence here. However, their worldwide tax liability is significantly restricted under provisions of the Income Tax Act (TVL). Special tax rules apply on the tax liability status of individuals employed by the State of Finland and of employees of the European Union. Section 4 below contains detailed instructions concerning their status and information on the tax treatment of their income. See also the Tax Administration’s guides Taxation of income from international organisations, the EU and diplomatic missions, Taxation of income earned abroad and Taxation of employees from other countries.

Tax treaties signed by Finland with other countries may limit the power to levy and collect taxes pursuant to Finnish national legislation if the individual’s treaty country of residence is not Finland. In such a case, the treaty country of residence generally has the right to tax the individual’s worldwide income, while Finland can only tax income the individual has received from Finland and only within the limits allowed by the treaty. For more information on the determination of the country of residence pursuant to a tax treaty, please see Section 5 of these instructions. Annex 1 at the end is an illustration of the impacts on Finnish taxes of an individual’s tax status, on the one hand, and of his or her treaty country of residence, on the other hand. The impact of tax treaties on the taxation of various types of income is discussed in more detail in the instructions Articles of tax treaties.

2 General information on applicable provisions and definitions

2.1 Tax residency pursuant to the Income Tax Act

Most provisions determining the scope of tax liability in Finland are in sections 9–13 of the Income Tax Act. Pursuant to section 9, subsection 1(1) of the Income Tax Act, individuals who lived in Finland during the tax year, Finnish organisations, benefits under joint administration and estates are considered resident taxpayers in Finnish income taxation. Organisations established and registered abroad with their actual headquarters located in Finland are also resident taxpayers. The Finnish Tax Administration’s instructions Yhteisön yleinen ja rajoitettu verovelvollisuus (Resident and nonresident tax liability of corporate entities) provide more information on the tax liability of organisations.

A natural person is a resident taxpayer in Finland if the natural person resides in Finland. Pursuant to section 11 of the Income Tax Act, an individual is considered to reside in Finland if they have their main abode and home in Finland. Furthermore, an individual who stays in Finland for more than six months is considered an individual residing in Finland. In the case of a resident taxpayer, taxes are levied in Finland for both income received in Finland and income received abroad (section 9, subsection 1(1) of the Income Tax Act).

An estate is considered a Finnish estate if the deceased resided in Finland when they died (section 14, subsection 7 of the Income Tax Act). A consortium or partnership is not treated as a taxpayer in itself in Finland. Instead, the income of a consortium or partnership is allocated to its shareholders and is taxable as the shareholders’ personal income. For this reason, consortia and partnerships are generally neither resident nor non-resident taxpayers.

The tax liability is not dependent on tax year or determined separately for each tax year. A party may be a resident taxpayer for part of a year and a non-resident taxpayer for the rest of the year (section 9, subsection 4 of the Income Tax Act). If an individual who used to permanently reside outside of Finland comes to Finland for a period of more than six months or permanently moves to Finland so that their main abode and home are in Finland, they will not be considered a resident taxpayer in Finland until as of the date of arrival. Similarly, a foreign citizen who moves from Finland generally ceases to be a resident taxpayer in Finland as of the date they leave Finland.

Finnish citizens who leave are generally still treated as Finnish tax residents during the calendar year when they move away and the three years that follow. However, an individual taxpayer who is a Finnish citizen may be considered a non-resident taxpayer as of the moving date, if they are able to demonstrate that all of their substantial ties with Finland were broken by the time of their leaving the country.

If they demonstrate that their substantial ties were broken after leaving the country, they may be considered a non-resident taxpayer only starting from the beginning of the next calendar year.

Pursuant to section 7, subsection 2 of the Income Tax Act, provisions on spouses only apply if both spouses are resident taxpayers. This may influence some deductions, for example.

Tax treaties and the Act on the Elimination of International Double Taxation (laki kansainvälisen kaksinkertaisen verotuksen poistamisesta, 1552/1995), prevent the occurrence of double taxation. However, the provisions of a tax treaty are of no significance when the authorities determine whether an individual is a resident or non-resident taxpayer in Finland. Instead, the authorities rely on the provisions of the Income Tax Act.

2.2 Nonresidency

The Income Tax Act determines who are resident taxpayers. A party that does not meet the characteristics of a resident taxpayer is a non-resident taxpayer. Whether a natural person or an organisation is a resident or non-resident taxpayer in Finland is always resolved solely based on Finnish national legislation. Hence, the provisions of any tax treaty are of no significance when determining tax liability.

All parties who are not resident taxpayers are non-resident taxpayers. If a natural person does not reside in Finland pursuant to section 11 of the Income Tax Act, the individual is a non-resident taxpayer in Finland. Special provisions apply to Finnish citizens, however (see Section 3.2). An estate is a non-resident taxpayer if the decedent was a non-resident taxpayer when they died.

Foreign citizens living abroad are non-resident taxpayers. If they come to Finland for a maximum of six months and they do not have a permanent residence or home in Finland, they remain non-resident taxpayers. As a general rule, Finnish citizens who have settled abroad, who moved abroad three or more years ago or who have, prior to moving, presented an account that they did not have any substantial ties with Finland during the tax year are non-resident taxpayers. However, Finnish citizens working in certain special positions abroad will not, in all cases, become non-resident taxpayers three years after having moved abroad. For more information on such special groups of taxpayers, please see Section 4 of these instructions.

2.3 Residency in Finland

Pursuant to section 9 of the Income Tax Act, tax residency is based on residency in Finland. Residency in Finland does not, however, necessarily refer to physically being in Finland; instead, it refers to residency in Finland as laid down in section 11 of the Income Tax Act, on which the tax residency is based.

Pursuant to section 11 of the Income Tax Act, natural persons are considered to reside in Finland and thus be resident taxpayers when

- they have their main abode and home in Finland; or

- they have a permanent home abroad but they reside in Finland for more than six months due to work, for instance, in which case a temporary absence is not considered as interrupting such a continuous period of residency; or

- they are Finnish citizens residing abroad who moved abroad less than three years ago and who have not demonstrated that they did not have substantial ties with Finland during the tax year; or

- they are Finnish citizens on a diplomatic mission abroad; or

- they are Finnish citizens employed by Business Finland abroad who were resident taxpayers in Finland immediately prior to the start of the employment abroad; or

- they are Finnish citizens in permanent full-time employment of the Finnish Government or specific international organisations abroad who were resident taxpayers in Finland immediately prior to the start of the employment abroad and who have not demonstrated that they did not have substantial ties with Finland during the tax year.

There is more information on all the groups listed above in the subsequent sections of these instructions.

2.4 Main abode and home

An individual is regarded as an individual living in Finland if they have their main abode and home in Finland. Here, the term “main abode and home” refers to a longer-term place of residence and a centre of specific personal interests. For example, a Finnish citizen may sometimes work several years abroad with their family and home remaining in Finland. They may also be recorded as an individual who has moved away from Finland in the Population Information System. Regardless, for taxation purposes Finland is still considered their main abode and home. On the other hand, merely having a residence in Finland does not necessarily mean that an individual has their main abode and home in Finland, provided that the residence in question is not the home of the individual and their family.

In general terms, an individual has their main abode and home in Finland if they are registered in the Finnish Population Information System. However, section 11 of the Income Tax Act does not include any reference to provisions on the Population Information System. Hence, whether an individual is regarded to have their main abode and home pursuant to the Income Tax Act in Finland is not dependent on whether the individual is or has been recorded in the Population Information System as an individual who lives in Finland. Even if the Population Information System does not contain an entry stating that an individual lives in Finland, they may still have their main abode and home in Finland within the meaning of the Income Tax Act (ruling KHO 26.5.1999/1275 of the Supreme Administrative Court). The actual conditions are assessed as a whole.

In most cases, a temporary residence does not meet the definition of main abode and home. The matter should not be assessed merely on the basis of the duration of residency, however. In some cases, even short-term residency may refer to the existence of a main abode and home if, for instance, an individual planned to permanently move to Finland but their circumstances changed during a short period of time so that they decided to live abroad instead. Thus, an individual who previously lived abroad may become a resident of Finland and a resident taxpayer in Finland even if they stay in Finland for less than six months, provided that during this time their main abode and home are in Finland.

An individual’s family living in Finland does not automatically mean that the individual’s main abode and home are in Finland if the individual has a home abroad (ruling KHO 1992 B 502 of the Supreme Administrative Court). In addition to the country in which the family lives, the country in which the taxpayer lives and works, and used to live and work, influence the overall assessment. In such cases, an individual may become a resident taxpayer in Finland based on residency if they stay in Finland for an uninterrupted period of more than six months.

2.5 Residency for longer than six months

In addition to the location of the main abode and home, tax residency may be based on residency in Finland. Someone who has previously lived abroad will become a Finnish resident taxpayer when they stay in Finland for a continuous period of more than six months. The residency will be considered continuous despite any temporary absence. For more information on temporary absence, please see Section 2.5.1 of these instructions.

The residency must last for more than six months – staying in Finland for exactly six months does not suffice. The six-month period is not dependent on the beginning and end of the calendar year. If an individual living abroad comes to Finland on 15 October and leaves Finland on 15 April, they will be considered a resident taxpayer in Finland for this period of time. They will be considered a non-resident taxpayer in Finland until October 14 the year they arrived and as of April 16 the year they leave. The dates of arrival and leaving will be included in the residency when assessing the residency in Finland.

Based on the wording of the law, it is the duration of residency in Finland that is relevant in the establishment of tax residency, whereas the reason for the residency is irrelevant – the individual may stay in Finland because of work or for another reason. Any kind of residency is considered when assessing an individual’s tax liability.

However, it has been deemed in case law that continuous residency will not be established if an individual living in Sweden close to the Swedish-Finnish border works daily in Finland but does not spend their nights in Finland (ruling 1987 II 506 of the Supreme Administrative Court).

2.5.1 Temporary absence and irregular residency in Finland

According to section 11 of the Income Tax Act, the residency of more than six months in Finland that leads to tax residency must be continuous and the residency will be considered continuous despite any temporary absences. The point of law does not state how long an absence may still be considered temporary. Case law does not specify any unambiguous limit either. In tax assessment practice, an absence of more than two months from Finland has usually led to the residency being no longer considered continuous. When an absence is considered temporary must be assessed on a case-by-case basis, however.

Example 1: A Polish musician leaves Finland for Norway. Prior to that, he has stayed in Finland for seven months. Two months later, he decides to move back to Finland. Under these circumstances, the counting of the six months of residency will be restarted from zero.

Example 2: Swedish employee A works in Finland for five months, goes to Sweden for a holiday of one and a half months and then returns to work in Finland for five months. The residency in Finland will be considered continuous from the start of the employment until the end of the employment, and the temporary absence in the middle does not interrupt the calculation of the period of residency. Thus, employee A is a resident taxpayer in Finland from the start of the employment until the end of the employment.

In addition to the periods of time spent in Finland and elsewhere, the situation prior to an absence influences the assessment. The decision may depend on, for instance, whether the individual still has a residence in Finland and whether their employment relationship is still in force while they are absent. If an individual’s main abode and home are in Finland, the residency and its interruption are irrelevant; their tax residency will continue for as long as their main abode and home are in Finland.

Example 3: Individual B, who permanently lives abroad, comes to Finland for two months, leaves the country for four months and then returns to Finland for two months. B will be a non-resident taxpayer throughout this period of time. The situation would be different in the case of, for example, a foreigner who has been staying in Finland for three years and whose main abode and home are in Finland. If such an individual leaves Finland for four months, they will remain a resident taxpayer in Finland for the period of four months if their main abode and home still are in Finland.

An individual who lives outside Finland on a permanent basis may also have a job that requires frequent short periods of staying and working in Finland. In case KHO 1990-B-501 at the Supreme Administrative Court, a Finnish company hired a factory consultant who lived in Sweden with his family. The length of the employment contract was more than six months. The consultant also worked abroad, and when he was present in Finland, it was for no more than four days a week. He spend his weekends and days off at his home in Sweden. His absences from Finland lasted from 3 to 29 days. The consultant was deemed to have continuously resided in Finland for more than six months. Hence, an individual may become a resident taxpayer in Finland also based on recurring short business trips.

Similarly, when an individual works in Finland on weekdays and returns to their family in another country for the weekends, their residency in Finland will be considered continuous and they will be a resident taxpayer in Finland. However, it has been deemed in case law that continuous residency will not be established if an individual living abroad works daily in Finland but does not spend their nights in Finland (ruling 1987 II 506 of the Supreme Administrative Court).

In tax assessment practice, recurring business trips may have been considered to establish tax residency if trips occur on average approximately on three or more days per week for a period of more than six months. If the residency in Finland remains below this limit, however, the individual is, as a general rule, a non-resident taxpayer. The conditions are always assessed as a whole on a case-by-case basis. One of the relevant facts during the assessment may be whether the individual has a residence at their disposal in Finland or whether they stay in a hotel during the business trips.

Example 4: Individual C who lives abroad with his family comes to Finland on business during a period of eight months (34 weeks) every week, spending 2–4 days per week in Finland. In total, he spends 108 days in Finland during that period of eight months. This means on average 3.18 days per week in Finland (108 / 34 = 3.18). As the residency continues for more than six months, C becomes a resident taxpayer in Finland.

Whether taxes are levied on his wages in Finland depends on the applicable tax treaty, his country of residence pursuant to the tax treaty and whether the company paying his salary is Finnish or not. However, tax residency means that C must file a tax return in Finland and request the application of any tax treaty. For more information on the taxation of wage income, please see the instructions Taxation of employees from other countries.

Example 5: Employee B from Estonia stays in Finland for two weeks at a time and then returns to Estonia for two weeks. The residency in Finland in such periods of two weeks continues for more than a year. The residency in Finland will be considered continuous and the temporary absences of two weeks will not interrupt the calculation of the duration of residency. Employee B is thus a resident taxpayer in Finland.

3 Ending of tax residency

3.1 Foreign citizen

The tax residency in Finland of a foreign citizen or an individual with no citizenship usually ends without delay when they move away from Finland. However, the tax residency of a foreign citizen may continue after they leave Finland if their main abode and home remain in Finland or they reside in Finland in a manner which leads to considering the residency continuous pursuant to section 11 of the the Income Tax Act for a period of more than six months.

3.2 Finnish citizens and the three-year rule

When a citizen of Finland moves abroad, a special provision included in section 11 of the Income Tax Act or the “three-year rule” usually applies. When a citizen of Finland moves to another country, they are normally regarded as a resident taxpayer in Finland for the year when they move away and the three following years. The tax residency will continue even if they no longer have their main abode and home in Finland and they do not continuously reside in Finland for more than six months. They may be considered a non-resident taxpayer prior to end of the third year after their move, however, if they request it and if they are able to demonstrate that they did not have any substantial ties with Finland during the tax year.

Based on request, a Finnish citizen who moves abroad in the middle of a tax year will be considered a non-resident taxpayer starting from the moving day if they are able to demonstrate that their substantial ties with Finland were broken at the time of leaving the country (ruling KHO 1981 T 3184 of the Supreme Administrative Court). In such a case, taxes can be levied in Finland after their move only for income received from Finland.

If the substantial ties were broken after the moving day but before the expiration of the three-year period, they have the right to request that they be considered a non-resident as of the beginning of the year when the substantial ties were broken. Thus, except for the moving day, the tax liability cannot start in the middle of a tax year (ruling KHO 2004:6). For more information on substantial ties and their breaking, please see section 3.3 of these instructions.

In most cases, a Finnish citizen is deemed a non-resident taxpayer after the period of three years if they do not have their main abode and home in Finland and they do not stay in Finland for any continuous period of more than six months after having left the country. Extending an individual’s tax residency in Finland for a period of more than three years solely based on the individual requesting this is not possible (see also Section 3.2.2).

As long as a Finnish citizen residing abroad is considered a resident taxpayer, their municipality of domicile during the year when they left Finland will remain as their tax domicile (section 5, subsection 2 of the Tax Assessment Procedure Act).

3.2.1 Temporarily or permanently moving abroad

If a Finnish citizen moves abroad, planning to study abroad for a maximum of 2–3 years and then return to Finland, tax assessment practice usually considers them a resident taxpayer in Finland for this period of time. The reason for leaving may be a work assignment or studies in the other country. Even though their main abode and home are not in Finland, they have substantial ties with Finland, as they have not permanently settled in the other country. Becoming a non-resident taxpayer based on a temporary move is thus uncommon.

The starting date of the nonresidency and the breaking of any substantial ties usually need to be considered in more detail in cases where the individual announces that the move abroad is permanent. The move being permanent in nature is a key prerequisite for the breaking of substantial ties. Matters speaking in favour of a move abroad being permanent may include the taxpayer having acquired a permanent residence or received a permanent job in the other country and thus being covered by the social security system of the new country of residence, or the taxpayer having married an individual who permanently lives abroad. The permanency of a move is always assessed from the perspective of the leaving of Finland and the settling abroad.

In some cases, a move that was supposed to be temporary becomes permanent and the residency abroad is continued. In these cases, it is possible that the calculation of the three-year rule will start from the actual year of leaving Finland.

The permanent or temporary nature of leaving Finland will be assessed from the perspective of substantial ties. All matters indicating permanent or temporary nature will affect the assessment, and a decision cannot be made based on a single fact indicating residency. In each case, a comprehensive assessment of the personal conditions will take place to determine whether the individual who has left the country has substantial ties with Finland.

3.2.2 When three years have expired

It is uncommon for a Finnish citizen who has moved their home abroad remaining a resident taxpayer in Finland after the three-year period. An exception to this rule are special groups of people who work abroad, such as individuals employed by the Finnish Government (see Section 4). If the individual is not included in any such special group, tax residency after the three-year period may mainly apply only if the Finnish Tax Administration demands it.

The purpose with section 11 of the Income Tax Act is to ensure that tax residency based on substantial ties after the expiration of the three-year period is only possible in exceptional cases. Such cases are uncommon, as in most cases the applicable tax treaty or, in the case of wage income, the six-month rule (section 77 of the Income Tax Act) eliminates Finland’s right to levy taxes on an individual’s income. If an individual does not have any income that could be taxed in Finland, their tax liability is of no practical significance. After the three-year period, the substantial ties must be especially strong for the tax residency to be still considered valid.

Exceptionally strong ties may be considered to exist if, for example, the taxpayer still has a residence intended for their own use in Finland as well as other ties, such as work or a family in Finland, and the taxpayer also spends a great deal of time in Finland. According to the interpretation adopted in case law (rulings KHO 1987-B-506 and KHO 1979-B-II-508 of the Supreme Administrative Court), the substantial ties must be clearly stronger after the three-year period than during the three years immediately following the move.

In practice, there may be cases where a taxpayer has been residing abroad for several years but has not moved from Finland in a manner that would have started the three-year period. In such cases, the tax residency may have been considered to be valid because the individual’s main abode and home were still in Finland. Similarly, the tax residency may persist if the individual still stays in Finland for a continuous period of more than six months.

3.2.3 Restart of tax residency

Once the substantial ties of a Finnish citizen are considered to have been broken and they have become a non-resident taxpayer in Finland, they can only become a resident taxpayer again if they move their main abode and home to Finland or they stay in Finland for more than six months. They cannot become a resident taxpayer based on any new substantial ties that appear at a later point in time (ruling KHO 1993-B-501 of the Supreme Administrative Court).

Sometimes, a Finnish citizen who has lived abroad for a long time returns to Finland temporarily but for a period of more than six months. If their main abode and home remain abroad after the residency in Finland, case law has considered that a new three-year period does not start when the visit to Finland ends (ruling KHO 28.2.1990 of the Supreme Administrative Court, court record no. 712). However, if an individual returns to Finland and moves their main abode and home to Finland, a new period according to the three-year rule will start if they move abroad again (ruling KHO 2013:93 of the Supreme Administrative Court).

3.3 Substantial ties with Finland

The provisions of law do not contain an exact definition of “substantial ties”. Instead, case law has been used as a guideline for how substantial ties should be determined. Substantial ties refer to a variety of personal and financial ties with Finland. A Government proposal (HE 40/1974) provides examples of facts indicating that an individual still has substantial ties with Finland: the individual has not settled at any specific location abroad, the individual stays abroad solely for reasons attributable to studies or health care, the individual practices business or owns real property in Finland or the individual’s family permanently resides in Finland.

The decision on the existence of substantial ties will be made on a case-by-case basis based on the overall circumstances, however. In most cases, if even one of the following conditions are met, substantial ties must be considered to exist during the first three years if

- there is a residence in Finland; or

- there is a spouse in Finland; or

- There is real property other than a summer cottage in Finland; or

- the taxpayer is covered by Finland’s residence-based social security benefits; or

- the taxpayer practices business in Finland; or

- the taxpayer works in Finland.

When assessing substantial ties, another relevant fact is how much time the taxpayer spends in Finland. If the taxpayer spends so much time in Finland that it constitutes as continuous in the manner laid down in section 11 of the Income Tax Act, the taxpayer will remain a resident taxpayer on this basis as well. Merely spending your holidays in Finland does not usually constitute tax residency, but it may affect the overall assessment.

The following sections discuss the interpretation of the substantial ties listed above. In addition to the substantial ties listed above, the impact of staying in Finland on the assessment is also discussed. It should be noted, however, that it is always a question of a case-by-case overall assessment based on the current conditions.

3.3.1 Permanent home in Finland

A key prerequisite for the breaking of substantial ties is the moving out of the country being permanent in nature. Typically, this means moving the whole family’s main abode and home from Finland with no intention of returning to live in Finland.

If the family’s permanent home that has been reserved for the family’s use or left vacant still remains in Finland after the move, the taxpayer is considered to have substantial ties with Finland. If the home has been sold or gifted in a manner that makes it unavailable to the taxpayer, a permanent home in Finland is no longer considered to exist. If the taxpayer has been unsuccessful in selling their residence due to a difficult market situation, for example, the residence will establish a substantial tie until it is sold (ruling KVL 1990/399 of the Central Tax Board).

As a general rule, substantial ties will not be broken even if the former permanent home of the taxpayer or their family is rented out. A home that forms a substantial tie may also be a residence other than the permanent home used by the taxpayer or their family if the residence can be used all year round and it corresponds to the living conditions of the taxpayer and their family. A residence owned or managed by the spouse may also be considered a substantial tie with Finland even if both spouses live abroad.

Example 6: Individual A moves with his spouse and children to Spain, planning to stay there indefinitely. For this purpose, they have purchased a home in Spain, but they decide to leave their home in Finland vacant so that they can use it when they visit Finland during their holidays. The residence in Finland is considered a substantial tie with Finland, and tax residency in Finland will continue for the year during which he moved and the three subsequent years.

In some exceptional cases where there is no other uncertainty about the breaking of the substantial ties, renting out the previous permanent home with a long-term lease, unfurnished, to a third party may be considered sufficiently significant relinquishing of the home to consider that the substantial ties were also broken in terms of the home. As a general rule, however, renting out the abode will not break the substantial ties.

Example 7: "B", an individual taxpayer, has a permanent job which requires him to leave Finland for Sweden. His moving out of the country is permanent in nature. He has owned a home in Finland that has been available for him to live in. He tries to sell it but is not successful, so he offers the home for rent instead. As a general rule, to continue to own a home that remains in Finland is considered a substantial tie, even that home has been rented to a third party. The tax residency in Finland will continue until the end of the year of moving and for the three subsequent years.

When assessing the substantial ties of a taxpayer as a whole, the ties of their spouse with Finland may also be relevant even though, as a general rule, the substantial ties of spouses are separately assessed. Taxpayers leaving Finland cannot break their substantial ties by transferring all of their assets to a limited-liability company that they own, to the taxpayer's spouse, or to some other party. Substantial ties can be considered to exist even if the taxpayer’s spouse is the sole owner of the residence in Finland that could be used as the family’s home all year round.

A summer cottage or a residential property that was acquired as an investment and has not been used and could not be used as the family’s permanent home does not constitute a substantial tie with Finland. However, a residential property that was acquired as an investment can influence the overall assessment to a greater extent than the ownership of listed shares, particularly if the taxpayer owns several such properties and the renting out of the properties requires active input by the taxpayer in Finland.

If the substantial ties of a taxpayer have been broken once and the taxpayer has become a non-resident taxpayer in Finland, purchasing a new residence suited for use all year round in Finland will not re-establish the substantial ties. For more information on the restarting of tax residency, please see Section 3.2.3 of these instructions.

3.3.2 Spouse or family

Usually, a taxpayer moving from Finland does not break their substantial ties with Finland if their spouse or family remain in Finland. The spouse or family remaining in Finland often supports the idea that the taxpayer still considers Finland as the centre of their vital interests and that the move is temporary in nature.

As a general rule, “family” consists of spouse as laid down in section 7 of the Income Tax Act and underage children. Pursuant to section 7 of the Income Tax Act, individuals who married prior to the end of the tax year are considered spouses. Individuals who live in the same household and were previously married or have or have had a child together are also considered spouses. Co-habitants other than those mentioned above are thus not considered spouses pursuant to the definition of section 7 of the Income Tax Act. Children who are over the age of 18, other relatives or any other individuals are not considered relevant when assessing substantial ties.

Example 8: "A", an individual taxpayer, has a permanent job which requires him to leave Finland for Sweden, the moving out of the country being permanent in nature. A’s spouse decides to stay in Finland with the couple’s underage child. The family in Finland constitutes a substantial tie with Finland even though A permanently moves to Sweden. The tax residency in Finland will continue until the end of the year of moving and for the three subsequent years.

A spouse or family remaining in Finland merely to handle practical matters related to the move, i.e. in order to follow the taxpayer abroad once the matters have been settled, does not usually constitute a substantial tie with Finland.

An estranged spouse with whom the taxpayer no longer lives and with whom they no longer plan to live, provided that the spouses have sought or will seek divorce, does not constitute a substantial tie. A decision from the District Court on the ending of the relationship can be applied but such a decision is not, as a general rule, required for taxation purposes to prove that the relationship has ended. Underage children who remain in Finland do not constitute a substantial tie, provided that the spouse living in Finland has received custody and the children live with the spouse. Joint custody of children does not constitute a substantial tie either, provided that the children will only be living with the spouse who remains in Finland.

Example 9: Individual B moves to Germany due to his permanent job, planning to stay there indefinitely. B has applied for divorce from his spouse Y, and the former spouses have agreed that Y will get custody of the couple’s children, and the children will live with Y in Finland. B plans to come to meet his children on two weekends each month. Alone, the former spouse and the children living with her do not form a substantial tie with Finland. If all other substantial ties were also broken at the time when B moved abroad, B may become a non-resident taxpayer as of the moving day.

The significance of a spouse and children as a substantial tie must be considered as part of the whole. A move and marrying another person abroad may confirm the idea that the move abroad is permanent in nature (ruling KHO 18.9.1979 of the Supreme Administrative Court, court record no. 3838).

3.3.3 Working or doing business in Finland

A taxpayer will be considered to have substantial ties with Finland if they work in Finland or practice business in Finland. Such financial ties requiring active input are considered stronger in the assessment of substantial ties than financial ties that do not require any active input on the part of the taxpayer (such as owning listed shares).

“Practicing business” refers to operations that require active input from the taxpayer in Finland. The company form is not relevant in the assessment. More importance is attached to whether or not the operation demands active performance of tasks and regular trips to Finland.

Finland’s Supreme Administrative Court handed down its ruling no KHO 2021:172 recently, which addresses the question of how an individual taxpayer’s circumstances should be appraised when a limited-liability company was wholly owned by the individual - the company’s business operation consisted of investments. The individual was also the company’s Managing Director and a member of the Board of Directors. The individual also owned some smaller amounts of stock in other Finnish limited companies as well, and was a Board member in a few of them. The substantial ties with Finland only consisted of financial and economic commitments because the individual had broken his other ties. According to the Court’s ruling, this means that an appraisal is needed of whether he must visit Finland on a regular basis and perform tasks in Finland in an active manner. It does not automatically mean that an individual taxpayer conducts business in Finland if he or she owns shares, either the entire corporate stock or a part of it, in a limited-liability company, and is a member of the Board or a holder of another similar position. If the taxpayer does not arrive in Finland on a regular basis and does not perform tasks in an active manner in Finland, the stockholding and managerial position alone are not enough to constitute substantial ties. Accordingly, if no other substantial ties exist, his or her tax residency in Finland is not treated as having continued past the date of leaving Finland. In the same way, the mere holding of stocks in a Finnish limited-liability company is not treated as a substantial tie with Finland if the taxpayer-shareholder does not take part in the business operation. However, from the perspective of an overall evaluation of a particular taxpayer’s circumstances, the existence of ties similar to the ones described above can be important. These ties could be combined with the taxpayer’s other ties with Finland and, for example, evaluated together with facts making it evident that he or she still receives the major part of annual income from the stockholdership with the Finnish company.

In most cases, sitting in the Board of a listed company or an unlisted limited liability company not wholly or partially owned by the taxpayer is not considered the practicing of business in Finland. However, sitting in the Board of such a company may be considered a substantial tie if the Board membership requires working in Finland.

Example 10: "A", an individual taxpayer, has a permanent job which requires her to leave Finland for Sweden, the moving out of the country being permanent in nature. “A” owns the entire corporate stock in X Oy, a Finnish company, and is the chairperson of the company’s Board and simultaneously, the Managing Director. Because of company business, she travels to Finland on a weekly basis. The conclusion is that “A” conducts business in Finland, which constitutes a substantial tie with Finland. Her tax residency in Finland will continue until the end of the year of moving away and for the three subsequent years.

Example 11: Having a permanent job that requires it, “A” leaves Finland for Sweden, the moving out of the country being permanent in nature. He owns the entire corporate stock in Y Oy, a Finnish limited-liability company, and is the chairman of the company’s Board and the company's Managing Director. Y Oy engages in an investment operation that mainly involves shares in stock-exchange-listed companies. It is not necessary for “A” to work in Finland. Instead, he performs his tasks working from Sweden, with the only exception of the annual general meetings of shareholders in Finland. He travels to Finland to participate in the annual general meetings. If all other substantial ties have also been broken, “A” can be treated as being a non-resident taxpayer immediately when he moves away from Finland.

Example 12: Individual A moves to Sweden due to his permanent job, planning to stay there indefinitely. A owns the shares of Finnish company X Oy but does not participate in the operations of the company in any way (does not sit on the Board and is not involved in any operational activities). Merely owning the shares does not constitute a substantial tie with Finland. If all other substantial ties have also been broken, A may become a non-resident taxpayer as of the moving day.

The practice of extensive renting operations may also constitute a substantial tie with Finland. This refers to, for instance, renting out several residences located in Finland, provided that active input by the owner is required and the income or assets are of major financial significance.

Permanent employment and working in Finland constitute a substantial tie with Finland. In case law, working has been considered to constitute a substantial tie also in the case of a part-time job (ruling KHO 1979-B-II-508 of the Supreme Administrative Court). According to tax assessment practice, however, temporary or insignificant work in Finland, for a maximum of a couple of days per month, is not necessarily considered a substantial tie with Finland, provided that all other substantial ties have been broken. Working for a private Finnish employer abroad does not constitute a substantial tie with Finland.

Example 13: Individual A moves to Germany, planning to stay there indefinitely. A still has an employment contract with a Finnish company and A plans to visit Finland weekly on business. A still has substantial ties with Finland. Thus, A’s tax residency will continue until the end of the year of moving and for the three subsequent years.

3.3.4 Being covered by Finland’s residence-based social security benefits

Being covered by the Finnish social security system constitutes a substantial tie with Finland. Residence-based social security benefits are especially relevant. Alone, the fact that Finland is, pursuant to EU Regulation 883/2004 on the coordination of social security systems, obligated to compensate for the medical treatment expenses of a pension recipient to the new country of residence if the new country of residence is an EU/EEA state or Switzerland does not constitute a substantial tie.

In the case of a permanent move from Finland, the Finnish social security coverage often expires on the moving day. If the move is meant to be temporary, however, it is possible that the individual will remain within the scope of the Finnish residence-based social security benefits for a specific period of time even if they are living and working abroad. Hence, inclusion in the scope of the Finnish residence-based social security benefits constitutes sufficient grounds for substantial ties with Finland.

3.3.5 Real property in Finland

In most cases, owning real property in Finland constitutes a substantial tie with Finland. As a general rule, the relevance of residential properties is assessed in the same way as the owning of residences (see Section 3.3.1). Property ownership often involves either owning a property suitable for residential use in Finland or active input in order to acquire or maintain income in Finland.

According to case law, spending holidays in Finland or having a holiday home in Finland does not constitute a substantial tie with Finland, provided that the taxpayer does not have any other substantial ties with Finland. Holidays or the ownership of a leisure home may therefore be significant in the overall assessment.

Example 14: Individual B has permanently moved to France. He owns a detached house in Finland, which he has rented out to a third party. Even though the property is not B’s former permanent home in Finland, it is not a summer cottage and thus it constitutes a substantial tie with Finland. B’s tax residency will continue until the end of the year of moving and for the three subsequent years.

Example 15: Individual A has permanently moved to Estonia. He owns a summer cottage in Finland, where he spends his summer holidays. Merely having a summer cottage and spending holidays in Finland does not constitute a substantial tie with Finland. A may become a non-resident taxpayer as of the date of moving, provided that his other substantial ties have been broken.

Non-residential properties may be considered less relevant in the assessment than residential properties. Such properties may include forest estates, for instance, provided that the ownership is passive in nature. If the taxpayer owns a significant number of properties, the ownership may require active input in Finland (such as working in Finland) to the extent that substantial ties are considered to exist.

3.3.6 Other income and assets

Substantial ties do generally exist only because an individual receives capital income from a Finnish source. If the individual must perform considerable work effort due to the management of their assets in Finland (also see Section 3.3.3), however, it may be considered as a substantial tie with Finland. However, if a taxpayer moves abroad with their family and the only assets remaining in Finland are of a passive nature and income received from such passive assets, they will not be considered to have any substantial ties with Finland (ruling KHO 2004:6 of the Supreme Administrative Court).

In the case of other income and assets, whether the income and assets are passive in nature and whether they require active input from the taxpayer are relevant. Passive assets include listed shares and bank deposits, for example. They are not considered as strong ties as assets requiring active input, such as ownership in a family business. When assessing financial ties, whether most of the taxpayer’s income is still accrued from Finland is also relevant. Sometimes financial ties are so strong that they alone constitute a substantial tie with Finland (ruling KHO 1989/190 of the Supreme Administrative Court).

Income that is considered passive in nature also includes pension and benefits income from Finland (such as motor vehicle or accident insurance payments), because no active input on the part of the individual is required in order to receive the income. Except for pension income, obtaining earned income from Finland is, as a general rule, considered a stronger tie with Finland than capital income. Pension income may still play a role in the overall assessment. Most individuals receiving benefits income (child allowance, maternity allowance, etc.) are covered by the Finnish social security system, which alone is considered a substantial tie.

Example 16: Individual A moves permanently to Norway due to his job. A’s ties with Finland consist of shares in a family business (share of ownership 60%), Finnish listed shares and fund units, as well as three leisure properties that A rents out to third parties. If the running of the family business and the rental activities require active participation on A’s part or working in Finland, A can be deemed to have substantial ties with Finland also after the move. In such a case, the tax residency in Finland will continue until the end of the year of moving and for the three subsequent years.

Example 17: Individual A moves permanently to Denmark due to his job. A’s only ties with Finland are Finnish listed shares and fund units. A may become a non-resident taxpayer as of the date of moving, provided that his other substantial ties have been broken. The ownership of listed shares and fund units is ownership of a passive nature, which alone does not constitute a substantial tie with Finland.

3.3.7 Significance of residency in Finland

One of the factors influencing the assessment of substantial ties may be the amount of time spent in Finland. If the taxpayer stays in Finland to such an extent that the residency is continuous pursuant to section 11 of the Income Tax Act, the individual is a resident taxpayer in Finland in any case.

The amount of time spent in Finland may be relevant when assessing whether the moving from Finland is permanent in nature or whether the residency or other substantial ties lead to believe that this is a temporary arrangement or that the taxpayer’s main abode and home actually remain in Finland. Even though the main abode and home were deemed to have been moved abroad and the taxpayer did not spend any continuous period of more than six months in Finland, the amount of time spent in Finland and the reason for spending the time in Finland will be relevant in the overall assessment if the taxpayer has other ties with Finland. Merely spending holidays in Finland does not constitute a substantial tie with Finland.

4 Special groups laid down in the Income Tax Act

4.1 Foreign missions of Finland

People in the service of Finland’s diplomatic and other missions abroad may either be part of the posted mission staff or hired locally (at the country of posting). The Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland determines whether an individual is part of the posted mission staff or hired locally. The taxation of the individual will be determined on the basis of the classification by the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland.

Finnish citizens in the service of Finland’s diplomatic and other missions abroad remain resident taxpayers in Finland throughout their service, provided that they are part of the posted mission staff (section 11, subsection 2(1) of the Income Tax Act).

If an individual is not a member of the posted mission staff, they are locally hired. In this case, the individual in question is in other permanent full-time employment of the Finnish Government abroad (section 11, subsection 3 of the Income Tax Act). Locally hired individuals are considered resident taxpayers throughout their service if they were resident taxpayers in Finland immediately preceding the signing of the employment contract. The three-year rule does not apply in these cases.

However, a locally hired employee may be considered a non-resident taxpayer if they request to be treated as such and if they are able to demonstrate that they have not had any substantial ties with Finland during the tax year.

If an individual has been considered a resident taxpayer in Finland due to service in a foreign mission, they may become a non-resident taxpayer immediately after the end of their service, provided that three years from the moving abroad have expired when their service ends.

If an individual has become a non-resident taxpayer in Finland already before the start of their service, they will not become a resident taxpayer merely because of their service in the foreign mission; instead, they will remain a non-resident taxpayer, unless they are hired as part of the posted staff of the foreign mission (section 11, subsection 2(1) of the Income Tax Act).

The place of tax residence of the family members of employees serving in foreign missions is determined on the basis of the general regulations on residency.

For more information about the status of employees of Finland’s diplomatic missions and about the tax treatment of their wages and pay, see Taxation of income from international organisations, the EU and diplomatic missions.

4.2 Business Finland Oy

A Finnish citizen working for Business Finland Oy (previously Finpro Oy/Suomen Ulkomaankauppaliitto r.y.) abroad is considered a Finnish resident and thus a resident taxpayer, provided that they lived in Finland immediately preceding the signing of the employment contract (section 11, subsection 2(2) of the Income Tax Act). The tax residency in Finland will not be interrupted even if their main abode and home are abroad, they do not reside for continuous periods of more than six months in Finland and three years have expired from the move. However, if the individual had become a non-resident taxpayer in Finland prior to the start of the employment, they will not become a resident taxpayer merely based on their employment with Business Finland Oy.

Individuals employed by Business Finland Oy may be commercial secretaries, for instance, and they may have diplomatic status in the country of posting. In such a case, they are not considered residents of the country of posting in terms of taxation. The six-month rule pursuant to section 77 of the Income Tax Act does not apply to their wages. Due to the 183-day rule, the country of posting often has the right to levy taxes on the individual’s wages, in which case the wages are taken into account in Finland using the credit or exemption method, depending on the tax treaty.

It is also possible for an employee of Business Finland Oy not to have diplomatic status in the country of posting. In such a case, they may be considered a resident of the country of posting pursuant to the tax treaty. If the work takes place in the country of posting, the tax treaty usually prevents Finland from levying taxes on the individual’s wages even though the six-month rule pursuant to section 77 of the Income Tax Act does not apply.

If an individual has been considered a resident taxpayer in Finland due to employment with Business Finland Oy, they may become a non-resident taxpayer in Finland immediately after the end of their employment, provided that three years have expired from them originally leaving Finland.

For more information on taxation of payments made and expenses reimbursed by Business Finland Oy, please see the Finnish Tax Administration’s instructions Taxation of work abroad.

4.3 Other permanent employment with the State of Finland

Finnish citizens employed by the State of Finland with permanent employment contracts and working abroad but not in a Finnish diplomatic mission, are considered resident taxpayers in Finland throughout their employment, provided that they lived in Finland immediately prior to signing the employment contract. The three-year limit does not apply in such cases. However, an individual may be deemed a non-resident taxpayer if they request it and are able to demonstrate that they did not have any substantial ties with Finland during the tax year (section 11, subsection 3 of the Income Tax Act).

If an individual has become a non-resident taxpayer in Finland already before the start of the employment, they will not become a resident taxpayer merely because of the employment. The provisions of section 11, subsection 3 of the Income Tax Act do not apply in such cases. The said point of law does not apply to honorary consuls, either.

If an individual has been considered a resident taxpayer in Finland due to employment with the State of Finland, they may become a non-resident taxpayer in Finland immediately after the end of their employment, provided that three years have expired from them originally leaving Finland.

Finnish citizens in the UN peacekeeper forces abroad (UN soldiers) are Finnish tax residents. They have an employment contract with the State of Finland, not with the United Nations. For example, an individual who received wages for working in Cyprus as a member of the UN Battalion was treated as having received income subject to Finnish taxation (ruling 1978 II 514 of the Supreme Administrative Court).

4.4 Employees of the EU

EU officials, who are subject to the protocol on the privileges and immunities of the European Union, should, in accordance with Article 13 of said protocol, be for taxation purposes considered residents in the Member State where they lived at the time of entering the service of the Union. When a Finnish resident taxpayer enters the service of the Union, they will remain a Finnish resident in accordance with Finland’s national legislation as well as the tax treaty between Finland and the country of work.

Pursuant to the protocol on privileges and immunities, an official who has left Finland to become an EU official will remain a Finnish resident taxpayer even if more than three years have passed since the year they moved abroad. In this respect, the provisions of the protocol on the privileges and immunities regarding tax liability override the provisions of national legislation (ruling KHO 2011:88 of the Supreme Administrative Court). Before issuing the ruling, the Supreme Administrative Court requested a preliminary ruling from the Court of Justice of the European Union, which, in its ruling no. C-270/10, decreed that an EU official shall remain the resident of their country of origin for the duration of their term of office.

Based on the protocol, the spouses and children of EU officials are also Finnish resident taxpayers if they are not engaged in any gainful employment of their own. If the spouse works for a local employer, even to a limited extent, the matter of their residency will be decided on the basis of the general provisions.

For more information on the tax liability of EU officials and the taxation of income from the European Union, please see the Tax Administration’s guides Taxation of income from international organisations, the EU and diplomatic missions, Taxation of income earned abroad and Taxation of employees from other countries.

4.5 Other special groups

For more information on the tax liability of individuals employed by international organisations and the diplomatic missions of foreign countries in Finland and the taxation of income from these positions, please see the Tax Administration’s guides Taxation of income from international organisations, the EU and diplomatic missions, Taxation of income earned abroad and Taxation of employees from other countries.

5 Impact of residency pursuant to tax treaty on taxation

5.1 General on tax treaties

Tax treaties on income taxation signed by Finland may limit the taxation right pursuant to Finnish national legislation. Tax treaties are bilateral or multilateral agreements made by Finland that assign the taxation rights of personal income between Finland and the other contracting countries.

International treaties between Finland and foreign states may limit Finland’s taxation rights in the case of both resident and non-resident taxpayers. A tax treaty may also completely prevent the taxation of income in Finland. Tax treaties also include provisions on double residency, i.e. situations where a resident taxpayer in Finland is also liable to pay taxes for worldwide income in another country. In some double residency cases, Finland is forced to waive its right to levy taxes on worldwide income for the benefit of the other country.

In the case of resident taxpayers, the limiting effect of a tax treaty may also be Finland being forced to eliminate double taxation as the country of residence pursuant to the tax treaty. As a general rule, this is done by Finland deducting from the taxes it levies taxes paid for the same income abroad (the credit method). Sometimes a tax treaty requires using the exemption method, in which case no taxes are to be paid in Finland for the income abroad. The income will, however, influence the taxes levied on other income in Finland (the progressive exemption method).

Annex 1 at the end of this instruction is an illustration of the impacts on Finnish taxes of an individual’s tax status and of his or her treaty country of residence. For more information on the impact of tax treaties on the taxation of various types of income, please see the instructions Articles of tax treaties. For more information on the elimination of double taxation, please see the instructions Relief for international double taxation.

The liability to pay taxes in Finland may also be limited by international social security conventions and the Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the coordination of social security systems (883/2004). In terms of taxation, these conventions are only relevant for the determination of the medical care contribution and the daily allowance contribution, as well as the employer’s health insurance contribution. For more information on the determination of the employee’s and employer’s health insurance contribution in international cases, please see the Finnish Tax administration’s instructions Taxation of income earned abroad and Taxation of employees from other countries.

5.2 Determination of residency pursuant to a tax treaty

The provisions of tax treaties on residency determine which country is considered an individual’s country of residence pursuant to the tax treaty. In the OECD Model Tax Convention, these provisions on country of residence are included in Article 4.

Pursuant to the tax treaty provisions on country of residence, an individual is considered a resident of a tax treaty country if they, according to national legislation of a contracting country, are a taxpayer in that country due to their place of residence, business management or similar grounds.

Tax treaties also include provisions on double residency, i.e. situations where a resident taxpayer in Finland is also liable to pay taxes for worldwide income in another country. If both countries consider the individual a resident of the country, when applying the tax treaty, they will be considered a resident of the country in which they have a permanent home. If they have permanent homes in several countries, they will be considered a resident of the country with which they have closer personal and financial ties (the centre of vital interests). In most cases, an individual’s country of residence pursuant to a tax treaty can be determined on the basis of the above-mentioned permanent home or centre of vital interests.

If a decision cannot be reached on in which country the individual’s centre of vital interests is located or if the individual does not have a permanent home in any country, they will be considered a resident of the country in which they are permanently residing. If they are permanently residing in several countries or no country, the country of residence will be determined on the basis of their citizenship. If an individual is a citizen of several countries or is not a citizen of any country, the competent authorities of the contracting countries will resolve the question of country of residence by means of mutual agreements.

The following sections provide more information on the determination of the country of residence pursuant to a tax treaty. For more detailed recommendations on the interpretation of each tax treaty provision, please see the commentary on the OECD’s Model Tax convention, Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital 2017, which is used, according to the case law of the Supreme Administrative Court, as an aid when interpreting specific tax treaties, provided that they correspond to the Model Tax Convention (ruling KHO 2016:71 of the Supreme Administrative Court). As the provisions on country of residence in some of the tax treaties signed by Finland may be different from the article on country of residence in the OECD Model Tax Convention, the provisions on country of residence must always be verified from the applicable tax treaty.

5.2.1 Tax residency

Pursuant to the tax treaty provisions on country of residence, an individual is considered a resident of a tax treaty country if they, according to national legislation of a contracting country, are a taxpayer in that country due to their place of residence, business management or similar grounds. It is a question of individuals with tax liability for worldwide income in the said country.

If an individual is a non-resident taxpayer in Finland, they cannot be considered a resident of Finland pursuant to a tax treaty. In such a case, they may be considered a resident of the other contracting country, unless there is reason to suspect that they do not have tax liability for worldwide income in the other country either.

If an individual is a resident taxpayer in Finland and a non-resident taxpayer in the other contracting country, their country of residence pursuant to the tax treaty is Finland. If they are a resident taxpayer in both countries, the country of residence pursuant to the tax treaty will be determined using the criteria laid down in the tax treaty.

In most cases, tax residency in another country starts after residency of around six months and is based on the national legislation of the country. As a general rule, the determination of tax residency requires a certificate from a tax official in the other country (a residence certificate).

National legislation of some countries includes special provisions that may limit an individual’s worldwide tax liability. If an individual is not liable to pay tax for worldwide income in the other country and their tax liability is limited, they cannot, as a general rule, be considered a resident of the said country pursuant to the tax treaty. This view is corroborated by a number of tax treaties, under the respective treaties’ Article 4, by virtue of the provision stating that “resident of a Contracting State” does not include any person who is only liable to tax in that State in respect of income from sources or assets located in that State.

However, if the worldwide tax liability of the individual is not limited in the other Contracting state but specific types of income are prescribed as tax-exempt, this will not prevent considering the individual a resident of the other Contracting state pursuant to the tax treaty.

Example 18: Individual A moves to China for a period of three years due to a work assignment. China does not consider A liable to tax on his worldwide income. A remains a resident taxpayer in Finland and the country of residence pursuant to the tax treaty is Finland for the duration of the assignment in China.

Example 19: Individual B is a resident taxpayer in Finland. He has left Finland to start living in Spain. He submitted an application to the Spanish authorities for the special tax status offered to persons who arrive from other countries ("Special Tax Regime", Lex Beckham). The Spanish tax agency has stated that people under Special Tax Regime are not deemed as tax residents of Spain for purposes of the tax treaty. For this reason, when the Finland–Spain tax treaty is applied, individual B cannot be held a Spanish resident for treaty purposes; instead, B’s country of tax residence is Finland.

5.2.2 Permanent home

If an individual is a resident taxpayer pursuant to national legislation in both contracting countries of the tax treaty, the first assessment criterion when determining the country of residence pursuant to the tax treaty is the location of their permanent home. In such a case, the country in which the taxpayer has a permanent home is considered the country of residence pursuant to the tax treaty.

The “permanent home” as referred to in tax treaties refers to longer-term residency that is not temporary in nature. Temporary residency in another country for a limited period of time does not, as a general rule, change an individual’s country of residence. In tax assessment practice, a “longer-term residence” usually refers to a home acquired for at least one year.

The home may be owned or rented. The type of tenure is of no significance when assessing the nature of residency; what matters is whether it is a residence that was acquired for use of a permanent nature or whether it is temporary accommodation for travel on business or studying, for example.

If a residence located in Finland has been rented out to a third party, it will not be considered the taxpayer’s permanent home when assessing the country of residence pursuant to the tax treaty. Here, the interpretation is different from a situation where an individual has requested nonresidency and rented out their residence in Finland. When assessing nonresidency, a residence in Finland will be considered a substantial tie even if it has been rented out to a third party.

Example 20: Individual A moves to Sweden for a period of three years due to a work assignment. A acquires a residence in Sweden for himself and rents out the residence he owns in Finland to a third party for the duration of the work assignment. A is considered a resident taxpayer pursuant to national legislation both in Sweden and Finland. As he has a permanent home only in Sweden, his country of residence pursuant to the tax treaty is Sweden.

5.2.3 Centre of vital interests

If an individual has a permanent home in several countries, the country of residence pursuant to the tax treaty is assessed on the basis of their personal and financial ties (centre of vital interests). Factors that are relevant in this assessment may include family and social ties, professional, cultural and political activities, the practicing of business or the location of assets. The case-to-case assessment of the centre of vital interests is based on the individual’s overall situation and the circumstances.

In most cases, “personal ties” refers to the taxpayer’s family. During the assessment, personal ties are often considered more significant than financial ties. Many countries consider the country in which an individual’s family lives as the centre of the individual’s vital interests.

If a Finnish citizen works abroad and is only residing abroad because of the work, their family still lives in Finland and the individual spends most of their free time in Finland, the country of residence pursuant to the tax treaty is Finland. On the other hand, if a foreigner comes to Finland for a work assignment of a couple of years with their family, their country of residence pursuant to the tax treaty is Finland in most cases.

Example 21: Individual A moves with his family to Sweden due to a work assignment of two years. The family’s residence in Finland remains available to the family and the family also acquires a residence in Sweden for the duration of the work assignment. As A has a permanent home in both Finland and Sweden, residence pursuant to the tax treaty is determined on the basis of the centre of vital interests. As A is living in Sweden with his family for the duration of the work assignment, A is considered a resident of Sweden for the duration of the work assignment when applying the tax treaty.

Example 22: Individual B, who is employed by an international group of companies in Germany, moves with his family to Finland due to a work assignment of two years. The family’s residence in Germany remains available to the family and the employer leases a detached house in Finland for the family for the duration of the assignment. As B has a permanent home in both Finland and Germany, residence pursuant to the tax treaty is determined on the basis of the centre of vital interests. As B is living in Finland with his family for the duration of the work assignment, B is considered a resident of Finland for the duration of the work assignment when applying the tax treaty.

5.2.4 Habitual adobe

If a decision cannot be reached on in which country an individual’s centre of vital interests is located or the individual does not have a permanent home in any country, they are considered a resident of the country in which they permanently (habitually) spend time.

When assessing the residency, residency in the individual’s permanent home (if any) and residency at any other location in the country in question are relevant. The residency is investigated for a longer period of time and short-term residency in another country does not usually have an impact on the determination of country of residence pursuant to the tax treaty. A more decisive factor in tax assessment practice is in which country the individual spends more time.